GM’s exclusive Guidestar navigation was available on a select handful of early 90s Oldsmobiles for a very short period of time. Gone as quickly as it arrived, the expensive system was at the forefront of in-car automotive navigation. Believe it or not, it was Oldsmobile that offered the very first navigation system for a passenger vehicle in the North American market. But what happened to Guidestar that led it to be featured here at Abandoned History? The tale begins in 1966, with a genius idea.

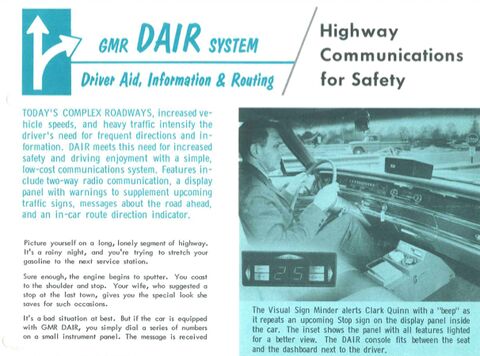

General Motors held an early interest in automotive navigation systems, and its Research Laboratories division worked on its first in-car system back in 1966. Called D.A.I.R., for Driver Aid, Information, and Routing, the system was far from navigation in the sense of the word today. It relied on 1960s technology, sans satellites.

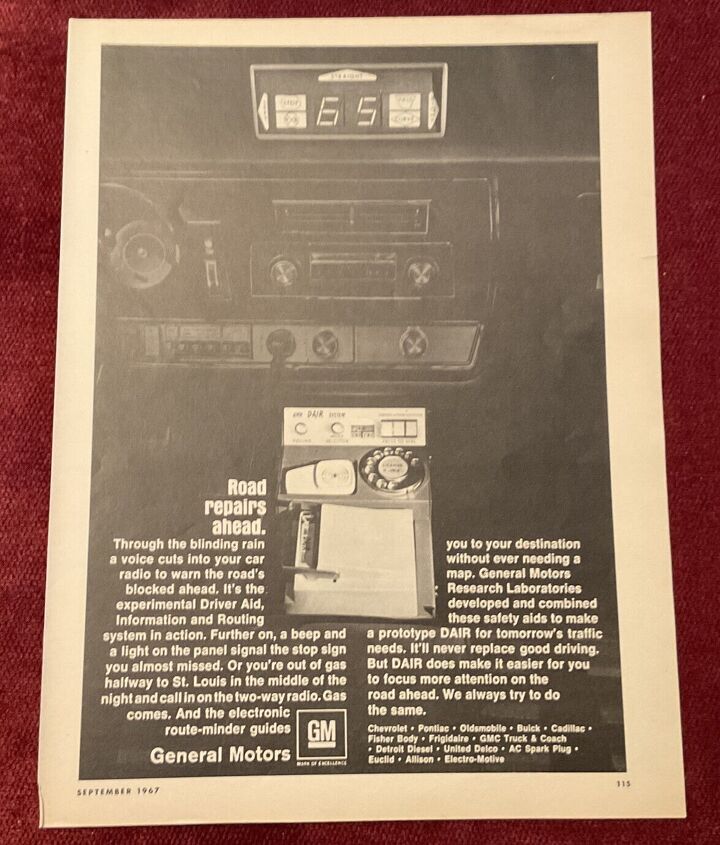

Two test cars were fitted with DAIR systems, and driven on a scaled-down version of an interstate at GM’s testing facility in the greater Detroit area. DAIR’s party piece was the real-time conveyance of messages about road conditions, signs, and hazards via the display panel mounted to the dash and voice recordings. The warnings were accompanied by route guidance along a preselected route. Further, both test cars used rotary telephone dials in the center consoles matched to CB radios, to send coded messages in real-time.

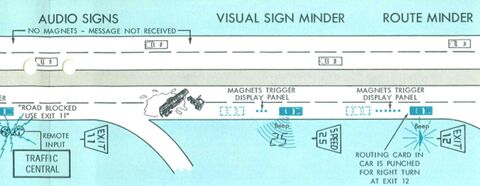

The panel itself was made of arrows, warning lights, and buzzers, which worked to alert drivers to issues, indicated when to turn left or right, and gave a heads-up about upcoming obstacles in the road. Warnings included vocal transmission into the car for traffic bulletins and accommodations and services on the road ahead. These warnings and mappings worked via three different methods that communicated in tandem.

Navigation points were provided via magnets that were buried underneath the road surface, spaced between three and five miles apart. Also along the road were communication modules that pinged the car as it passed, and could alert the nearest service center if the time between signals was too long. Finally, coded communication was provided to and from the system via radio, courtesy of the FCC Citizens Band radio frequency.

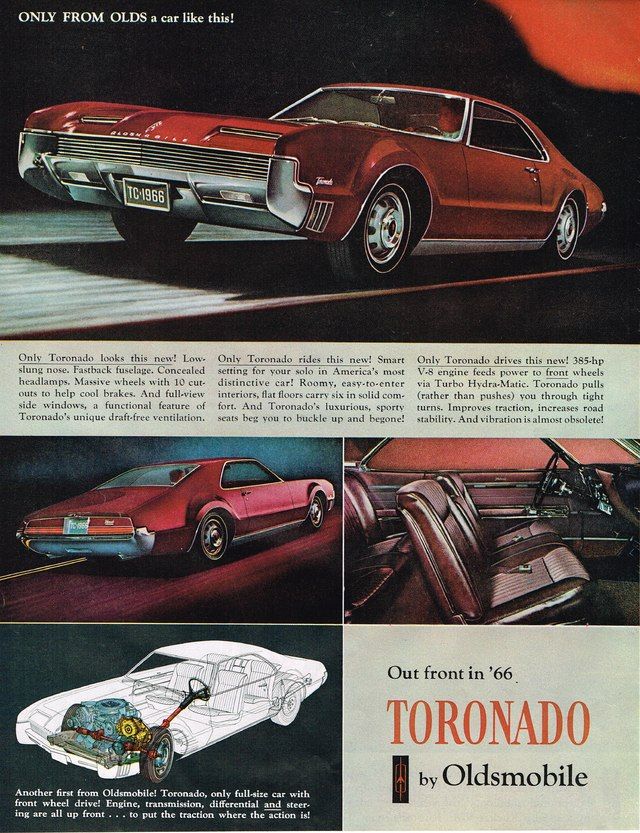

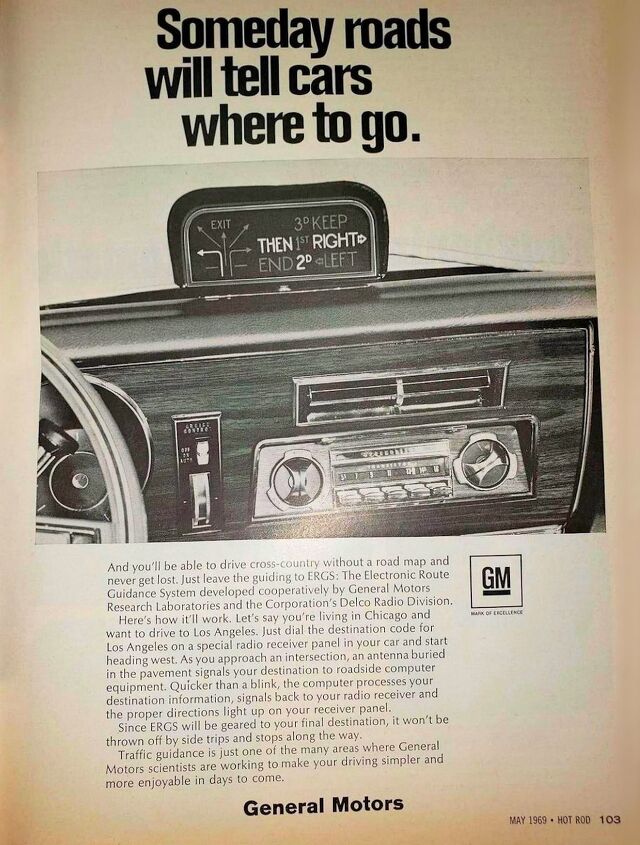

Those three methods put together provided enough information for route guidance, which GM called the “route minder.” You can almost picture the font they’d have used in a ‘66 Toronado for its labeling. Route minder required another accessory, a punched-out card like those used in early business computers.

Punched segments in the card informed the system of the desired destination. The card fit into a slot on the center console, which identified major intersections along the route. The system received feedback from the magnets buried in the road at all intersections, and compared that to the punch data on the card.

That meant DAIR could give a left, right, or straight direction to keep a driver on the correct course, making sure magnetic feedback matched where the vehicle was supposed to go. The idea behind this was a network of buried magnets underneath each major intersection in the nation. By that method, a magnetic mapping would be created, and allow cross-country travel via the magic of magnetic fields.

The coded magnetic information was of further use to emergency responders, too. In the pre-cellphone era, the driver could use the telephone dial in the console to dial up a code for the particular type of distress. Calling up a tow truck, the police, or a fire department via CB code, DAIR relayed information about the particular vehicle and its location.

GM’s engineers realized this could pose a security risk, should the message about distress and location be intercepted. Messages were encoded so only the correct recipients could understand. That’s right, it was the earliest conceptual version of what (decades later) became OnStar.

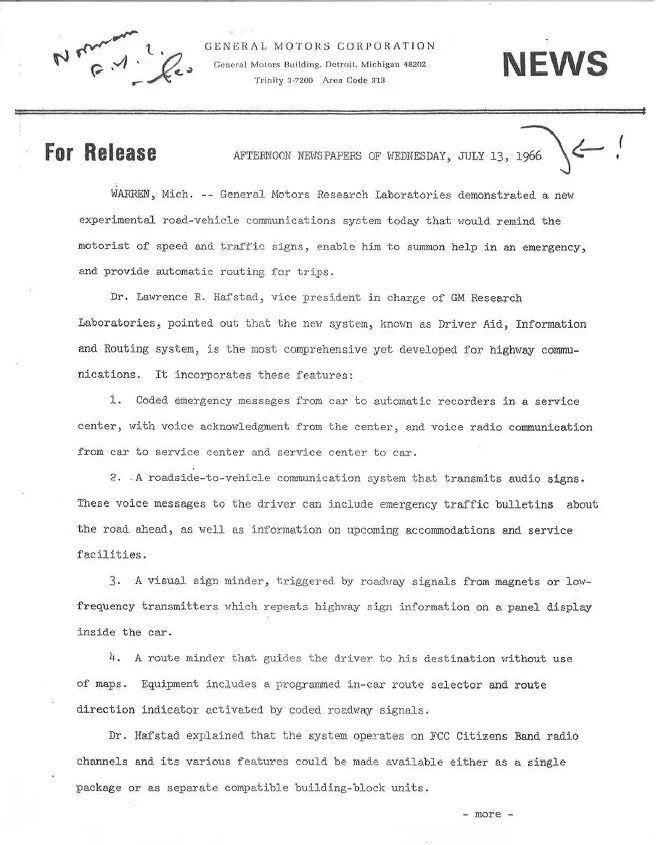

There was a press release from GM on July 13, 1966, about the DAIR system, which touted the comprehensive nature of its highway coverage and explained its features. The General was serious about this project and it was headed by the Research Laboratory’s vice president, Lawrence R. Hafstad (1904-1993). Hafstad wasn’t any old engineer, as in 1939 he created the first nuclear fission reaction in the United States. Thinking of the future, Dr. Hafstad suggested the features of DAIR could be sold as an overall package, or offered separately à la carte.

GM went as far as to publish ads for the system in magazines as late as September of 1967. At some point thereafter circa 1969, a later iteration of the project renamed it to ERGS or Electronic Route Guidance System. It appeared to be a standalone guidance system that did not incorporate warnings or emergency location and substituted punch cards for a destination code on the car’s radio receiver.

Updating every major intersection across the country with magnets was technically possible and would have led to a national navigation system that could theoretically be used by all manufacturers, the government, and the military. But it was a monumental ask. Imagine securing permission from every state and county government to cut holes in all the intersections and install communication modules at certain distances. Impossible.

The experimental program never moved beyond two cars equipped with the system and was quietly discontinued. DAIR’s original idea of emergency services and location functionality was eventually reborn as OnStar, but not until some 30 years later in 1996. But between DAIR and OnStar, General Motors made two additional attempts at in-car navigation. We’ll pause there and pick up next week with local governments, rental agencies, Mazda, and Toronados.

[Images: General Motors]

Become a TTAC insider. Get the latest news, features, TTAC takes, and everything else that gets to the truth about cars first by subscribing to our newsletter.

from TheTruthAboutCars https://www.thetruthaboutcars.com/cars/features/abandoned-history-oldsmobile-s-guidestar-navigation-system-and-other-cartography-44503162?utm_medium=auto&utm_source=rss&utm_campaign=all_full

No comments:

Post a Comment